Their medium may be old-fashioned, but Mexico’s folk balladeers, known as corridistas, have a unique power to shape the opinions of Mexico’s poor through their morbid yet lively songs called corridos. Nowadays, the corridistas’ most popular songs speak of the lives and legends of narcotraficantes, or drug lords: who they were, what they did, who they killed, and, often, how they died. Through these polka-like songs, Mexican drug-lords are not only glorified but mythologized. Corridos, like some perverse form of public relations, have an incredible capacity to define the popular perception of a narcotraficante. In this way, the corrido has become an invaluable tool for Latin America’s drug-lords; tales of their mercilessness and brutality strike fear in the hearts of their enemies and their own inner-ranks -- and the listening public can’t get enough.

Definition of Corridos

In musical terms, Corridos are “eight-syllable, four-line stanzas sung to a simple tune in fast waltz time, now often polka rhythm” (Dickey, 2001). Américo Paredes, a scholar of the corrido of the lower Rio Grande border area, believes that corridos were brought to Mexico as Spanish ballads from the Conquistadores. Paredes notes that the word corrido is derived from the Andalusian phrase romance corrido, which refers to a rapidly-sung romance. With the pronoun dropped, the participle corrido -- from the verb meaning “to run” -- then became a noun.

Subject Matter of Corridos

Corridos became increasingly popular during the Mexican Revolution of 1910 – 1918, according to Dan Dickey of the Texas State Historical Association. He explains that these folk ballads described current events as seemingly banal as a migrant worker’s journey to the field or as spectacular as a revolutionary hero’s death, the capture of a bandit, a bullfighter’s demise, a barroom shootout, or even a train wreck. Each, however, centered on a theme of heroism. Relevant here is Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death, in which he explains, “Society provides the second line of defense against our natural impotence by creating a hero system that allows us to believe that we transcend death by participating in something of lasting worth” (XIII). In this way, corridos offer an excellent example of how culture can establish different types of heroism – in this case, stucturing status, roles, customs, and rules of behavior amongst criminal elements just the same as revolutionary war heroes.

Early Distribution Methods for Corridos

Art historian, Melody Mock, tells us more about the corridistas, themselves. According to her, these musicians generally traveled from one market to another singing the corridos and selling cheaply printed copies of the lyrics, often illustrated by the renowned Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada (see Appendix II). Mock notes that corridistas sang accompanied by a regular guitar and “bajo sexto,” a kind of 12-string guitar. The original audience for corridos comprised poor people from semi-literate levels of urban and rural society. Thus, the illustrated corridos served as an “audio-visual” means of communication for those who could not read. Perhaps the spectacle of death in corridos found favor among poor people simply because they took comfort reveling in the fact that, affluent or poor, everyone is going to die someday.

Formal Conventions of Corridos

Beyond the music, the rhymes, and the subject matter, corridos have other important conventions. In his book La lírica narrativa de México, Vicente Mendoza writes that there are six important characteristics in a corrido.

(1) the initial call of the corridista, or balladeer, to the public, sometimes called the formal opening; (2) the stating of the place, time, and name of the protagonist of the ballad; (3) the arguments of the protagonist; (4) the message; (5) the farewell of the protagonist; and (6) the farewell of the corridista.

It’s important to note, as these conventions indicate, that the corrido is almost always a mourning song. In Mourning and Melancholia, Freud describes mourning as a “reaction to the loss of a loved person, or to the loss of some abstraction which has taken the place of one, such as one’s country, liberty, and ideal, and so on.” Corridos mourn the death of an ideal: the ideal of a better life, of success and riches. Because, in the end of a corrido, the hero has to die and never is able to enjoy the glory of success.

Narcocorridos and Los Tigres del Norte

Returning to the historical research of Dan Dickey, he writes that in the late 1940’s and 1950’s when “Tex-Mex” music became commercialized, so did the corridos. In those times, a new subject to sing about emerged : drug smuggling. This is the origin of the narcocorrido, or “Mexico’s own style of gangsta rap” (Hodgson, 2004). Martin Hodgson, in his article Death in the Midday Sun, offers an excellent example. Here, he describes the song “El Avión de la Muerte” (The Plane of Death) as performed by Los Tigres del Norte, the most popular corridos band in history:

Over a rollicking accordion line, it narrates how Atillano (famous drug lord) is captured by the Mexican army, and tortured until he agrees to fly them to the cartel's secret landing strip. Once in the air, he disarms one of the soldiers, seizes control of the plane and snarls that he'd rather die than squeal.

It's a magnificent, ridiculous song, equal parts grotesquely, sentiment and melodrama. It's also completely true: air traffic controllers recorded the whole sorry incident. This is narcocorrido, a music steeped in the blood and gun-smoke of Mexico's drug wars.

This is one of the many drug-related songs that Los Tigres del Norte has written and performed over the years. This famous Mexican band started in 1968 and is made up of three brothers (Jorge, Raúl and Hernán Hernández) and a cousin (Oscar Lara). They started to play their grandparents’ instruments in cantinas, and like thousands of immigrants, crossed the border to make it in America (Quiñones, 1998). Their first hit came in 1970 and told the tale of two rival drug dealers. However, in 1972, their song “Contrabando y Traición” (“Contraband and Betrayal”) became a target for controversy. Not only did it talk about drug smuggling but of love and betrayal: how a woman killed a man before he could abandon her. Why would the act of murder committed by a woman spark such controversy? In Mexican culture, steeped in “macho” ideals, this was absolute transgression. Bataille’s tells us that, “Such a divinely violent manifestation of violence elevates the victim above the humdrum world where men live out their calculated lives. To the primitive consciousness, death can only be the result of an offence, a failure to obey” (Bataille, 82).

Censorship

After Los Tigres’ “Contrabando y Traición” song, other corridistas continued writing narcocorridos. Since nearly every song tends to end in the violent death of the protagonist, narcocorridos were censored by several major radio stations in Mexico because educated, wealthy Mexicans and the Catholic Church would complain about the scandalous lyrics. Of course, as is always the case, prohibition breeds desire. Geoffrey Goer, author of The Pornography of Death, concludes that “people have to come to terms with the basic facts of birth, copulation, and death, and somehow accept their implications: if social prudery prevents this from being done in an open dignified fashion, then it will be done surreptitiously.” As a result, Los Tigres del Norte have been consistent bestsellers and their fame has grown to international proportions.

In an interview Hodgson conducted for his article, Jorge Hernández, leader and accordionist of Los Tigres del Norte, told him, “Poor people idolize the narcos (drug-lords): they admire their bravery and they want to be like them. When you sing the songs, the audience feels that they're living through the characters, as if they were watching a film. That's why people love the corrido. It lets them dream” (qtd. in Hodgson 2004).

Rosalino “Chalino” Sánchez

Even before Los Tigres del Norte, there was Rosalino “Chalino” Sánchez, a renegade artist from Sinaloa, a state in the north of Mexico that is well known for its abundant marijuana fields. Hodgson writes, “When he was 15, Sánchez shot and killed a man who had raped his sister, and fled to California, where for a while he worked as a 'coyote', smuggling illegal immigrants and drugs across the border. Only when he was arrested, and spent nearly a year in Tijuana prison, did he discover his skill at song writing. He began composing corridos for fellow inmates, and once outside, found his skills in demand from both dealers and legitimate immigrants.” While not the best singer, his incredible lyricism built his reputation quickly. Having earned his street credibility in jail, he soon afterwards was contacted by famous Mexican drug lords who would commission him to write songs about them and their criminal exploits. To shed some light on this fascination with death, we can turn to writer Margaret Atwood in her book Negotiating with the Dead: “All writing of the narrative kind, and perhaps all writing, is motivated, deep down, by a fear of and a fascination with mortality -- by a desire to make the risky trip to the Underworld, and to bring something or someone back from the dead” (157). Chalino, in this way, had a sought-after ability to immortalize the Mexican drug lords.

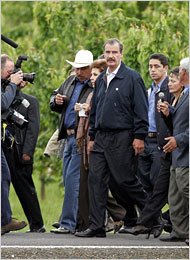

Chalino, himself, portrayed the brave image of the Mexican cowboy. After dealing with the narcotraficantes, he acquired both powerful friends and enemies. According to an informer that talked to Martin Hodgson, “The cartels used the group’s music to lay out a code of conduct for its members: ‘Through the corridos comes the philosophy, how the members of the cartel have to behave. If you listen carefully, the songs tell you what they did wrong. You learn what you have to do so they don’t kill you.’” At the same time, the death drug-lords became heroes through corridos. Some enjoyed their hero status while still alive, but most of them earned it after death. This returns us again to Becker’s introduction to Human Nature and the Heroic in his book The Denial of Death. He explains, “… [T]he problem of heroics is the central one of human life, … it goes deeper into human nature than anything else because it is based on organismic narcissism and on the child’s need for self-esteem as the condition of human life. Society itself is a codified hero system, which means that society everywhere is a living myth of the significance of human life, a defiant creation of meaning.” Hence, by commissioning corridistas to write about them, narcotraficantes could satisfy that narcissism and become heroes in their own right.

Chalino’s Murder

Since Chalino’s songs allied him with certain cartels, a number of opposing cartels were eager to dispose of him. He was shot during a concert in 1992, returned fire, and the incident became a gun battle where seven people were injured, and at least one was killed (Hodgson, 2004). Years later, he was murdered but the authorities never arrested the mysterious criminals. This event crowned Chalino as the “Mexican version of Tupac Shakur” (Hodgson, 2004), and – just the same – more posthumous albums were released than there were when he was alive. Due to the fact that there were no solid suspects in the crime, and no one to blame, Chalino’s murder earned mythological status. If one can’t put a name and a face to such a violent act, it is almost as if it never occurred. The person who dies becomes immortal in this way because, as Bataille explained, we are discontinuous beings but we obtain immortality through death -- the more violent, the more it transcends.

Conclusion

The modern corrido, beginning with Chalino and carried on by Los Tigres, sensationalizes death and crime for larger audiences than ever before. To the poor of Mexico, these tales of their country’s most notorious criminals have become contemporary fables. And for the drug lords, these songs have become essential tools for doing business in a ruthless industry. In a society largely unburdened by middle-class, bourgeois concerns, it would seem that heroes can be born even in the most unlikely of circumstances.

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. “Descent - Negotiating with the Dead: Who makes the trip to the Underworld, and why? Negotiating with the Dead: A Writer on Writing, Anchor, 2003.

Bataille, Georges. Eroticism: Death and Sensuality. San Francisco: City Lights, 1957.

Becker, Ernest. The Denial of Death. New York: Free Press/Simon Schuster, 1973.

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone Books,1994.

Dickey Dan W. “Corridos.” The handbook of Texas Online 6June 2001. 6 May 2006.

Hodgson, Martin. “Death in the midday sun”.The Observer Music Monthly. 19 September 2004. 6 May 2006.

Mendoza,Vicente T. Lírica Narrativa de Mexico: El Corrido. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Instituto de Investigaciones Esteticas, 1964.

Mock, Melody. Jose Guadalupe Posada and Corridos of the Mexican Revolution.

6 May 2006.

Stavans, Ilan. “Trafficking in Verse”.The Nation. 7January 2002. 6May 2006.

Quinones, Sam. “Corridos Prohibidos.” 4 November 1998. 6 May 2006.